Despite considerable advances in the medical field and care, and service delivery, inherent bias remains a persistent challenge in healthcare. Inequities affect not only the quality of care that different groups receive, but also critical outcomes, such as mortality and quality of life.

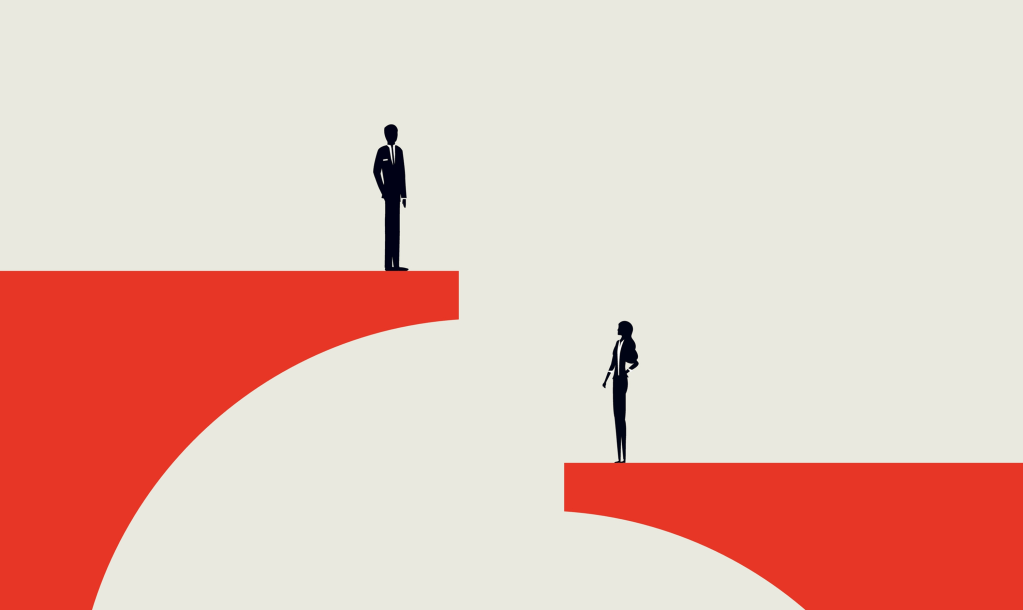

Gender Bias and ‘Medical Misogyny’

Recent investigations into women’s health reveal an alarming pattern in the treatment of female patients. The House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee (2024) report on women’s reproductive health conditions provides stark evidence that many women experience a systematic dismissal of their symptoms. The report states that there exists “a clear lack of awareness and understanding of women’s reproductive health conditions among primary healthcare practitioners” (para. 4). This phenomenon, often referred to as “medical misogyny”, leads to delays in diagnosing conditions such as endometriosis, adenomyosis and pcos, impacting not only physical health but also education, work, mental health, and social life.

The delay in accurate diagnosis translates into worse health outcomes over the long term, and women who suffer from prolonged undiagnosed conditions often experience chronic pain, reduced fertility, and mental health challenges. This leads to a poorer quality of life and, in severe cases, can contribute to increasing morbidity. Research indicates that early intervention is critical, and the failure to recognise and treat women’s health issues expedites adverse outcomes and escalates healthcare costs over time.

Socioeconomic and Class Disparities

Beyond gender, socioeconomic and class factors play a critical role in shaping health outcomes. Data from the Health Inequalities Dashboard (Department of Health and Social Care, Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, 2022) consistently show that individuals living in the most deprived areas suffer from markedly higher rates of premature mortality compared to those in affluent areas. Research by Marmot (2020) highlights that “life expectancy in the UK varies by up to 10 years between the most affluent and the most deprived areas,” demonstrating the stark class-based inequities.

Socioeconomic deprivation is closely linked to a multitude of adverse health outcomes, including higher rates of chronic illnesses, mental health disorders, and reduced access to preventive services. The stress of financial insecurity and poor living conditions contribute to higher incidences of conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses. Moreover, individuals in deprived areas frequently lack access to quality healthcare facilities, exacerbating delays in diagnosis and treatment. This creates a vicious cycle where poorer health further limits economic opportunities, perpetuating the cycle of disadvantage.

Socioeconomic disadvantage often intersects with racial bias. People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who are disproportionately represented among certain ethnic minority groups, often face compounded barriers including unhealthy living conditions, chronic stress and loneliness. Together, these factors contribute to the higher incidence of chronic illnesses and poorer overall health outcomes.

Racial Bias and Disproportionate Health Outcomes

Racial disparities in healthcare outcomes have, also, more recently come under intense scrutiny. Research from The King’s Fund (2023) reveals that people from ethnic minority groups frequently report poorer experiences when interfacing with health services. In fact, evidence shows that these communities are more likely to suffer from increased mortality rates and adverse health outcomes. A government analysis by Ali, Chowdhury, Forouhi, and Wareham (2021) highlights that people from Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Black ethnic groups endure a disproportionate burden of low income and deprivation which, as explored above, is strongly linked to suboptimal healthcare access and higher premature mortality.

These biases manifest in tangible differences in clinical outcomes. For example, delayed access to care often results in advanced disease stages at diagnosis. Patients from ethnic minority backgrounds may also experience poorer management of chronic conditions, resulting in an increased likelihood of complications. The compounded effect of racial bias not only erodes trust in the healthcare system but also leads to statistically significant differences in life expectancy and overall health status. As one report succinctly states, ethnic minority groups “are more likely to experience negative encounters with the healthcare system,” (The King’s Fund, 2023).

The Economic and Human Cost of Bias

The cumulative impact of these biases is profound. Gender bias not only delays diagnosis and treatment for women but also contributes to wider societal costs through lost productivity and increased long-term healthcare expenditure. Similarly, racial and socioeconomic disparities exacerbate the strain on health services and result in millions of premature deaths each year. The human cost, seen in the form of reduced life expectancy, debilitating chronic conditions, and poorer mental health, is mirrored by significant economic losses. For example, endometriosis, alone, is estimated to cost the UK economy £8.2 billion a year in treatment, loss of work and healthcare costs. By addressing these biases, the healthcare system could save valuable resources and improve overall societal wellbeing.

References

Ali, R., Chowdhury, A., Forouhi, N., & Wareham, N. (2021). Ethnic disparities in the major causes of mortality and their risk factors: A rapid review. Retrieved May 2025, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-commission-on-race-and-ethnic-disparities-supporting-research/ethnic-disparities-in-the-major-causes-of-mortality-and-their-risk-factors-by-dr-raghib-ali-et-al

Department of Health and Social Care, Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. (2022). Health Inequalities Dashboard: Statistical commentary, June 2022. Retrieved May 2025, from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/health-inequalities-dashboard-june-2022-data-update/health-inequalities-dashboard-statistical-commentary-june-2022

House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee. (2024). Women’s reproductive health conditions. Retrieved May 2025, from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5901/cmselect/cmwomeq/337/report.html

Marmot, M. (2020). Build Back Fairer: The Marmot Review Update. Retrieved May 2025, from https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/build-back-fairer-the-marmot-review-update

The King’s Fund. (2023). The health of people from ethnic minority groups in England. Retrieved May 2025, from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/health-people-ethnic-minority-groups-england

Leave a comment